Alison Klayman

49. Take Your Pills, directed by

Alison Klayman

Like Taking Candy Off A Baby

By Rose Marel

There’s something within human nature that drives us forward, urging us to achieve, and pressing us to surpass. Ambition, competitiveness and perfectionism intermingle in ways that can be both constructive and destructive. We see it throughout history: the space race, the arms race, or in fields predisposed to the public lauding of frontrunners, like entertainment or sport. Technological innovators and entrepreneurial minds push themselves towards advancement, and “Keeping Up With the Joneses” becomes impossible when the Joneses themselves are constantly on the move. Let’s face it, the Western World is a moving one, with people moving up and moving forward, escalating until we’re all inside an air-tight pressure-cooker.

And that’s where Adderall comes in.

Alison Klayman’s documentary Take Your Pills demonstrates that the impulse to succeed is one that can easily be exploited, and it is, mostly by companies primed to make a buck. More than a buck, actually, as the prescription medication industry today is valued at around $3 billion. The escapist ’60s and ’70s are considered the pinnacle of widespread, open and popularised drug use – the era of drugs, sex and rock and roll, the summer of love, and the psychedelic exploration of ‘tuning in and dropping out.’ While illegal drugs remain rampant today, in a modern context of excessive stimuli where competition is a defining aspect of society and work is inextricably entwined with life, for some the ‘tuning in’ becomes much more important than the ‘dropping out.’

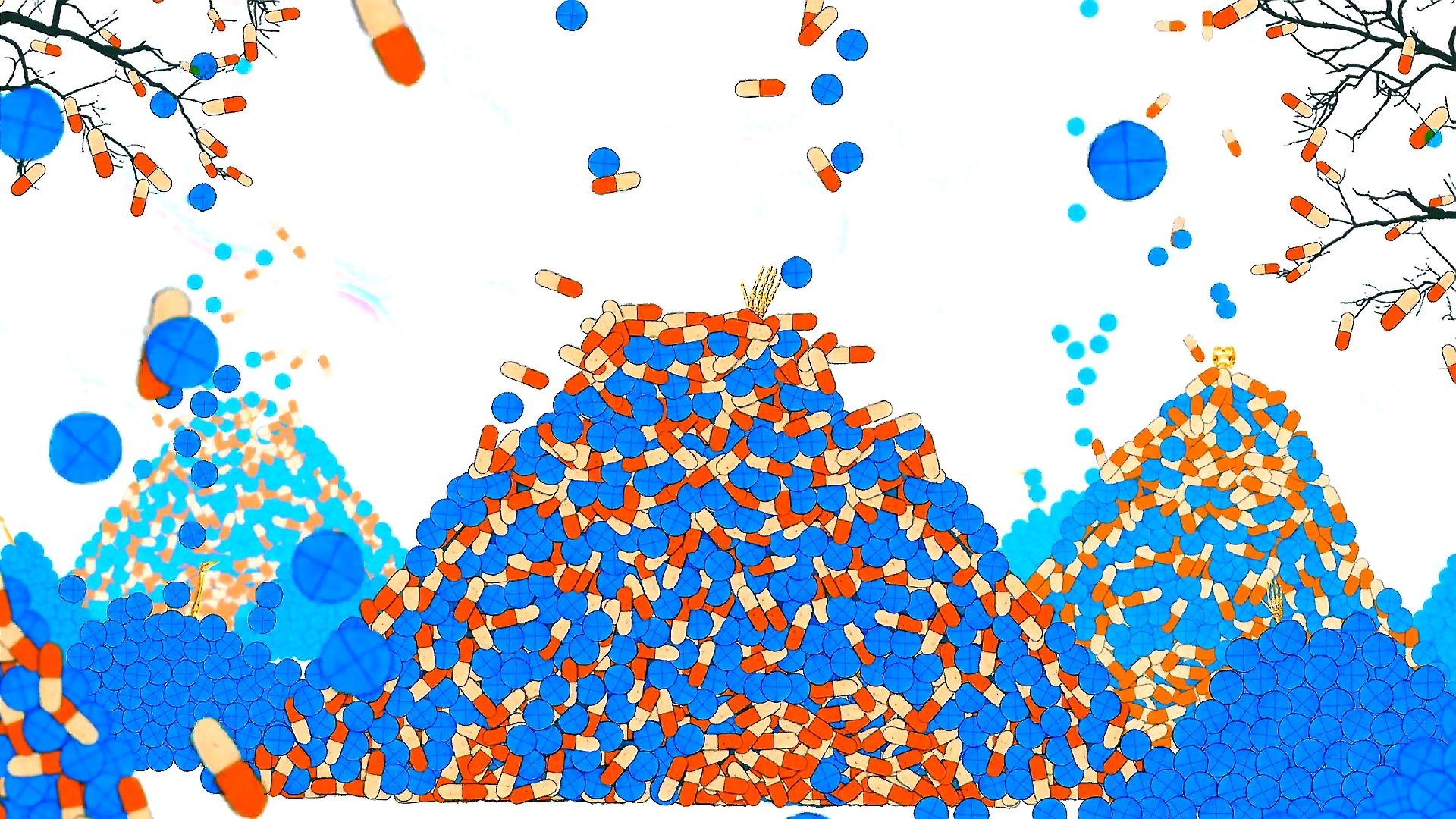

Like candy for our eyes, Klayman inundates us with bright visuals characterised by a gamified theme, one evocative of the bygone world of arcades. It’s at once nostalgia-inducing and oddly relevant, suggestive perhaps of our distancing from life – a modern tendency to reduce our communication to texts (an offshoot of our wider digitisation) and of our growing desensitisation. Visually, it’s less emotional and more directly stimulating. Whether or not that’s an intellectual stimulation or an attention-oriented one is another interesting idea to consider, and no doubt Klayman distracts us purposefully to play with the idea of our collectively dwindling attention spans and inability to slow down.

This is highly relevant to the main offender in Take Your Pills: Adderall. Prescribed as a medication to combat Attention Deficit Disorder, and designed for people who struggle to focus, Adderall has become a hugely used drug amongst both children and adults. The number of children prescribed the drug has increased rapidly in the US, from 600,000 in 1990 to 3.5 million in 2011. Even more shocking, adults have now become the fastest growing market for ADD medication and diagnosis. So, while Adderall is becoming more and more used, it is also statistically becoming more and more abused. And, as the world fills with even more distractions and attention spans decrease, concentration as a commodity becomes all the more valuable.

Those falling into the web of addy’s alluring appeal are managers like Blue, athletes (Eben Britton), programmers and college kids (Leigh and Delaney, respectively). Each of them, interspersed throughout the documentary, provides varied examples of the same thing: addy’s influence provides the alleviation of, and transcendence above, the pressures and distractions of working life. Whether it’s university or Wall Street, the ‘Pep Pills’, according to Rd. Wendy Brown, allow users to “perform at the highest capacity that you can and do it for as long as it takes.”

Klayman takes an effect-orientated approach to mirror this psychological experience of the drug. Working towards an immersive demonstration, the film whips itself into a visual frenzy, favouring flashing, overlapping images and kaleidoscopic effects. It’s purposefully stimulating until it reaches its own breaking point – trippy, coalescing graphics that build into a broken record, scratching and repeating before taking on a surrealist edge, transforming into rainbow, or blurring slightly at the edges. At other times, we stand outside the effects, watching the results – a tableau of intense concentration – as visuals accelerate around a studying individual who remains unmoving and single-minded in their task. Combining this dreamy feel with the scientific effect, Take Your Pills uses microscopic images of chemical structures that, magnified, dance trance-like across the screen.

Rifling through its historical context with black and white footage and animated re-creations of Adderall’s scientific development, we trace back to its birth and insidious infiltration into society throughout time. How it was synthesised as an allergy medication, but soon became a multi-purpose drug due to its feel-good side effects, trickling through the beatnik writers and jazz crowds and into the go-go, go-to crowds like Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick. Thus, it became part of a collectively accepted drug-using culture, approved and even endorsed by the widespread media.

Now, in a different time and age, and with more information about the harmful effects of what is, essentially, a rich-man’s relative to meth, Klayman predominately delves into the question of “Why?”. Why do people use it, and what does it say about our culture as a whole? Moreover, by claiming that we’re all “on the spectrum” and, therefore, entitled to mind-altering drugs, we bring up the moral implications of trivialising a real disorder. Is it right, and are your successes legitimate, if you’ve achieved them with the help of Adderall? As Leigh bemoans, it wasn’t really her, but “me and the Adderall”.

Klayman takes a fairly neutral stance, refusing to skew our perception one way or the other. We clearly see the rewards of such a drug, with testimonials tracing back through time, but underneath is a warning, reinforced by a skeleton motif that pairs with the examination of our fast-paced, competitive world. It’s easy to get caught up in the whirlwind of productivity and material advancement, but in an age that both values time and disregards it, the price to pay may be more than getting a ‘B’. Like pac man, chomping through time, spurred on by the sound of progress, it’s all too easy to get unexpectedly cornered and be chewed up yourself, in a sudden, petrifying collapse. And when that happens? Game over.